On May 17, 1963, the University of Rochester inaugurated its sixth president, W. Allen Wallis. In his inaugural address, Wallis invoked the ambitious and adventurous spirit of Captain James Cook.

His vision for Rochester students was one that had them seeking new horizons “driven by their own inner expectations and standard.” With this in mind, he offered that “To Each his Farthest Star” would make a fitting motto for Rochester—if it did not already have a fine one in Meliora.

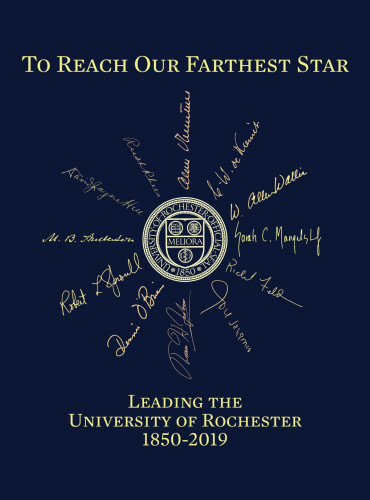

Although Wallis didn’t inspire a coup de motto, he was the source of inspiration for the title of Rush Rhees Library’s Great Hall exhibition To Reach Our Farthest Star: Leading the University of Rochester, 1850–2019.

The exhibit itself, which explores the many hats a University president must wear, was inspired by yet another president, the University’s first, Martin Brewer Anderson. Anderson told a friend that a college president:

is expected to be a vigorous writer and public speaker. He must be able to address all sorts of audiences upon all sorts of subjects. He must be a financier able to extract money from the hoards of misers, and to hold his own with the trained denizens of Wall Street. He must be attractive in general society, a scholar among scholars; distinguished in some one or two departments of learning; gentle and kindly as a woman in his relations to the students, and still be able to quell a 'row' with the pluck and confidence of a New York Chief-of-Police.

To Reach Our Farthest Star’s curator, Melissa Mead, the John M. & Barbara Keil University Archivist and Rochester Collections Librarian, provided a behind-the-scenes look at the exhibition.

Inaugurating a new president is a special moment in University history. Is this kind of exhibit a traditional way to celebrate it?

Absolutely. Our department records show that we’ve done retrospective exhibits for every new president going back to at least 1984 for the arrival of Dennis O’Brien.

Presidential exhibits are a way of reviewing University history, to document accomplishments and institutional milestones. And we did a historical overview exhibit in conjunction with the publication of Our Work is But Begun in 2014, also arranged by presidential tenure.

So, I wanted to try to do something different with this. It does include a timeline that notes the milestones, but the overarching approach was to take Anderson’s list of presidential abilities and map those to some of his own accomplishments and those of his successors.

What did you think about Anderson’s view on what a president should be?

I think he was probably being facetious, and yet accurately describing the expectations. At one time or another in a president’s tenure, all those abilities are tested, especially when external forces change the direction of a presidency. Anderson and Valentine both led during wars, and in Valentine’s case the institution had to focus completely on supporting the military effort.

Some presidents may not get enough credit for their accomplishments. President Hill inherited an institution that had not kept up with its peers. He expected the faculty to actively shape the curriculum, something Anderson had not considered. He had come from Bucknell, which was coeducational, and although women would not be admitted here as undergraduates until 1900, he opened the door just a bit. Hill started to sweep away the cobwebs, and laid the foundation for Rhees’s success.

Between 1951 and 1961, President de Kiewiet merged two colleges thus making us coeducational, added nine buildings, and opened three graduate schools. He was also actively traveling and speaking against apartheid in South Africa.

Was there anything in particular that you were excited to include?

I wanted to include our alumni, staff and faculty who became leaders at other institutions. For example, two of the four women who served as deans of the College for Women between 1910 and 1955—Helen Bragdon and Margaret Habein Merry—went on to become college presidents. Professor of English Ruth Adams was president at Wellesley College, and former Dean of Students Mary-Beth Cooper is currently president at Springfield College.

And there are many, many others who have done this—over 70 since Alexander Brooks (Class of 1851)became president of Gonzales College in Texas, in 1856.The idea I wanted to convey is that perhaps these individuals saw how things were done here and thought, “I want to emulate this somewhere else” or “I can do it better than that.” Their farthest star was to become a university or college president. ∎

To Reach Our Farthest Star will be on display into February of 2020. For questions on the exhibit, contact Melissa Mead. Enjoy reading about the University of Rochester Libraries? Subscribe to Tower Talk.