Whether it be dressing up a look-alike American Girl Doll or designing a Mii on Nintendo, recreating ourselves in different mediums is entertaining. However, whenever I’ve created my own character, it never ends up looking like an exact replica of myself. I’ve found that this is not an indication of a lack of craftiness on my end or design options in my chosen medium, but rather a manifestation of the empowerment that comes with being able to design a character that resonates with my identity—even if it calls for a divergence from my physical appearance. I might give my Mii a hair color that I’ve always dreamed of trying but haven’t been able to commit to. This is what is so entertaining about designing alternate versions of ourselves.

Now, creating avatars for games and Bitmojis is certainly fun and important in the realm of entertainment, but what if what if we could translate this true-identity-embodiment into the realm of therapy? Specifically, I’m proposing that we use VR as a form of therapy for body dysmorphic disorder (BDD). Those who struggle with body dysmorphia experience a highly distorted perception of their own appearance. For those of you who aren’t well versed in VR, I might sound a bit unhinged here. But I promise I’m not. I wouldn’t consider myself a VR whiz either, so I’d like to share with you my first VR experience—Richie’s Plank Experience to be exact—which made this idea slightly more tangible for me.

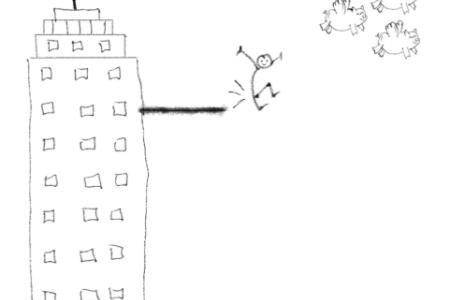

Suited up in the Meta Quest 3, I traveled to the top of a skyscraper and stepped out onto a wooden plank overlooking an utterly frightening drop. I *tiptoed* to the end of the plank, peered over the edge, and could not bring myself to jump. I repeated this routine multiple times, and after thirty minutes, I still hadn’t jumped. The day I jump from Richie’s Plank is the day pigs fly.

I offer this anecdote to highlight the extreme control VR can have over our psyche, to the extent that it could become a powerful tool in the realm of mental health. Regarding my proposed use of VR for BDD, in the same way that we can create idealized virtual versions of ourselves, perhaps we can create more realistic versions, allowing the patient to view an “updated” version of their body from the third person perspective. While the former experience allows individuals to deviate from

the norm and the latter attempts to bring them back to it, both utilize the same logic and methods.

When I first learned about the potential of VR as a form of therapy in Slater and Sanchez-Vives’ “Enhancing Our Lives with Immersive Virtual Reality,” I was skeptical. I didn’t question the power of VR; I’m pretty sure my brain chemistry was altered after doing Richie’s Plank Experience. Rather, I found myself doubting our ability to create out-of-body experiences through VR. After a little research, though, I learned that this type of manipulation is quite simple—despite its complexity, the brain can be as gullible as a toddler in some cases.

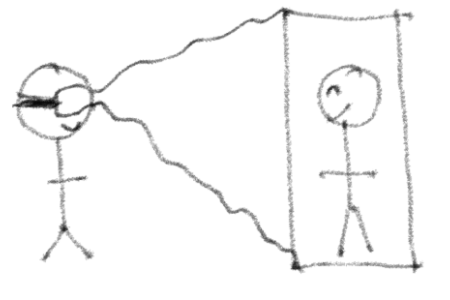

A classic example of this is the Rubber Hand Illusion (RHI), which can trick the brain into perceiving a fake limb as part of the body. In this experiment, the subject’s hand is hidden from view and replaced with a rubber hand. The real and rubber hands are stroked simultaneously and after a while, the brain integrates the tactile and visual stimuli, causing the subject to assume body ownership over the rubber hand. This experiment demonstrates just how powerful external cues, such as tactile stimulation, can be in altering our body representation. With the aid of VR, we can use similar techniques to create a full body illusion setup, allowing an individual to take ownership of a virtual body from the third person perspective. This might still seem entirely inconceivable. And if the scientific jargon didn’t do it for you, it didn’t for me either. You’ll just have to try VR for yourself; then you’ll understand. Try Richie’s Plank Experience. I promise.

Now that I have (possibly) convinced you that we are capable of creating out-of-body experiences in VR, I’d like to explain the therapeutic applications of this manipulation, specifically for individuals who struggle with BDD. Patients with BDD have a preoccupation with and accompanying distortion of their body image that is almost exclusively a conflict with oneself. Essentially, people with BDD don’t walk down the street and warp the physical appearance of those around them—their distortion is intrinsic. By shifting patients from the first person to the third person view, where they become an observer watching themselves walk down the street, we can challenge their perceptions and expose them to more accurate versions of themselves.

At the crux of this reasoning lies the Self-Perception Theory, which posits that “people infer their attitudes by observing their own behaviors and the context in which [they] occur.” If we apply this theory to VR therapy, when seeing themselves in a new light, patients will begin to reshape their attitudes about their own physical appearance. Over time, repeated exposure to more normalized versions of themselves will encourage patients to internalize these healthier attitudes. As the boundaries between reality and VR soften, and the patient identifies with their more realistic virtual body, the patient may experience relief from the distress caused by body dysmorphic thoughts.

At this point, with all those irresistible facts and theories, I’m confident that I’ve sold you. As much as I am rooting for this innovation as well, I would be remiss not to acknowledge its potential drawbacks. When it comes to BDD therapy, we are dealing with individuals who are already experiencing psychological distress, so it is important to consider the impact that the proposed manipulation might have. Even if this therapy attempts to revert a distorted body image back to a more realistic one, it still uses an illusion to do so. As Slater and Sanchez-Vives put it: “Virtual reality encompasses virtual unreality.” With this in mind, certain hesitancies arise for me. If the patient is unable to transfer their positive experiences in VR to the real world, they could become reliant on VR. In addition, those with BDD are in a compromised mental state, so seeing a radically different image of their body could cause an emotional overload or intensify their distress. Finally, it would be important to ensure that the VR depiction doesn’t reinforce unrealistic beauty standards but instead portrays the individual in a neutral, realistic light. That said, I do not suggest that we shy away from using this therapy; rather, I recommend that we place a greater emphasis on researching it.

I believe that if implemented correctly through a coordinated effort by therapists and VR experts, this therapy holds great potential. What do you think? In any case, you can find me at the top of Richie’s Plank, because I certainly haven’t jumped just yet.

Image Sources:

Headline Image

Image 1: Original

Image 2

Image 3: Original